P2: Search for Beauty

"Let us worry about beauty first, and truth will take care of itself."

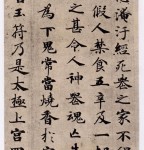

What is beauty? Philosophers pondering the meaning of aesthetics have produced weighty tomes, but an absolute definition of aesthetic values remains elusive. Aesthetic perceptions differ from culture to culture. Different conventions govern landscape painting in the East and West. If there is no objective standard of beauty in the world of human creations, what system of aesthetics are we to use in speaking of the beauty of the Nature? How are we to judge the Nature's design to benefit an artist’s creation? Or how a non-Chinese speaking people perceive the abstract beauty within a Chinese calligraphy work?

It is “perception” of our basic senses that drive us to make things better, be it for delicious cooking, melodious music or beautiful painting. However, everyone’s perception is different. So artists as well as critics “set” criteria for appreciating art and traditional rules and norms to create good arts. Why criteria for arts? And why do we need to learn traditional rules and norms? If art does not impose some norms or standards, then everybody can have it in his own way without learning and practicing. Consequently, people won’t appreciate each other’s ways. Just as languages and music have their own grammars, Chinese calligraphy has numerous sets of strict rules, norms, and esthetics.

For example, a major rule of Tsao Shu is to simplify the left radical of a Chinese character and focus on the right radical (“Yi Zuo Yang Yu 抑左揚右,” literally simplify the left and focus on the right.) This rule makes writing the left part of a character faster by connecting it from the right part of the preceding character.

Thus a calligraphy work in Tsao Style will look more smooth, connecting, and faster with abrupt turning and dramatic effects. The following is a chart that lists each character in Kai Style and three ways of writing that character in Tsao Style. Like Zuan Style, a character can be written in many ways in Tsao Style.

From the above examples, we may know “simplifying the left and focusing on the right” is the major rule for creating a Tsao Style character by different ancient calligraphers. The calligraphers obey the prototype more strictly on the left side while they have leeway for artistic design on the right side. If a laymen tries to coin his way of creating a Tsao Style character without learning, he may end up making mistakes. Adding or removing a single dot in one position can turn a Tsao Style character into another one. For example, “Wei #2” and “Zu #3” are just different in one dot in the beginning and another dot at the end. There are innumerous examples in Tsao Shu of tiny differences like this example since the total number of Chinese characters is so large.

However, rules are not absolute. A rule that is not allowed in one Chinese calligraphy style may be a specialized feature in the other styles. For example, Emperor Huei Zong ( 宋徽宗 ) of the Sung Dynasty invented Skinny Gold Style “So Jin Tee 瘦金體” that adopted strokes with principles against traditional rules and theories. It was “that” calligrapher’s perception that made him not to adopt traditional rules of most Chinese calligraphy methodologies and that made him unique and different.

The above left and middle Kai Style works were obeying the traditionally strict rules of Chinese calligraphy. However, the right one drastically deviate from the traditional rules of strokes. Those strokes look very speedy and sharp which are not seen in almost all other styles.

“In my own development as an artist, it has been made evident to me, time and time again, that success comes from the careful observance of details.” ~ Ferruccio B.Busoni. The first step to practice art will be “observing” and "understanding" rather than mere practice or creation by our physical hands. Some artists used to say that onehas "to train one's eyes." Before we start a piece for any forms of art, we must mentally “visualize” our design. This is very important in the Lin Mo ( 臨摹 )process of Chinese calligraphy. To be a Chinese calligraphy cognoscente both in skills and insight, one has to train his inner eyes to see the underlying principles guiding an ancient master’s design. He has to go beyond the extrinsic beauty as shown in the writing to the profound beauty embodied within. Then he may realize that the ancient Chinese calligraphy masters embodied cosmic harmony of structures and shapes within their masterpieces.

Physicists from Einstein on have been awed by the profound fact that, as we examine Nature on deeper and deeper levels, She appears even more beautiful. Why should that be? We could have found ourselves living in an intrinsically ugly universe, a “chaotic world," as Einstein put it, "in no way graspable through thinking."

Likewise when we look into the ancient Chinese calligraphy masterpieces on deeper and deeper levels, we will find the beauty of the calligraphers’ souls speaking in their own works. How did they do that? They simply observed and followed their inner heart. The more we dive in, the more we feel that the ancient wise men exceeded us in mental, physical, and spiritual levels. We are just living in a “chaotic world of deteriorating Chinese calligraphy bombarded with fame, shortsightedness, self-proclaim, politics, and lack of skills and consciousness.”

The essence of art is in the "eyes of the beholder" rather than permanently fixed, quantitatively and qualitatively, within the aesthetic object. Art is a special human behavior towards aspects of one's world that are determined to best give one the experience of feelings and meaning of great intensity, relative to other objects or aspects of our environment. The qualities of these "aspects" of our world that conjure up the feelings and perception of art include the masterful ability of the artist to include, in his aesthetic stimuli formation for others, the qualities of "comprehensiveness" (the degree to which the work creates the feeling of integration and unity in the viewer), "consistency" (elements of the work form a compatible whole), "intensity" (the creation of emotional intensity through both the form and content of the work), and "originality" (the value of novelty through creativity which leads to new aesthetic experience for the beholder).

The artist facilitates in his creation aesthetic perception of the viewer. The viewer must take responsibility for the carryover of aesthetic appreciation, from that of the artist that created the stimulus, to his own feelings and internalized relationship with the art object.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|

- 2011-05-06 - KUSHO: Calligraphy in The Sky, Shinichi Maruyama, Janpan Modern Art

- 2011-05-04 - Wang Xizhi, The Sage of Chinese Calligraphy

- 2011-04-23 - Ouyang Xun, one of the Four Great Calligraphers of Early Tang Dynasty

- 2011-04-07 - Chu Suiliang 褚遂良, one of the Four Great Calligraphers of Early Tang Dynasty

- 2011-01-07 - 文徵明行书《明妃曲》

- 2010-08-10 - Laozi (Lao-tzu, fl. 6th C. BCE)

- 2010-08-08 - The Dragon's Embrace - China's Soft Power Is a Threat to the West

- 2010-04-19 - The Core of Chinese Culture

- 2010-03-12 - Bringing it All Back Home: Chu Teh-Chun at NAMOC