Traditional pagodas and wooden sampan boats are common sights along West Lake in Hangzhou, once a refuge for painters and poets.

ON a misty afternoon in February, Lingyin Temple, a fourth-century Buddhist site that is one of China’s most important sanctuaries, felt more like a carnival than a place of worship. In large multigenerational packs, festive families were gathered for the Lunar New Year holiday, tossing fistfuls of ceremonial paper money into huge open fire pits and waving incense sticks as they jostled through crowds on their way to visit the 80-foot-high Buddha that is the building’s centerpiece. All the while they were downing fried tofu on sticks and corn on the cob and taking photos of everything on digital cameras.

My family and I, possessing the only Western faces in the crowd, qualified as a photo coup — especially my towheaded toddler. “Look over here, foreign baby!” a young mother shouted as she held up her baby next to mine. The holiday period may officially last only a week, but the celebratory mood in Hangzhou seems to have permanently taken over this ever more vital city.

Hangzhou has always held a near mythical status in China, both for its beautiful lakeside location and as a place for meditative and spiritual retreat in times of trouble. During the culturally rich but politically disastrous Southern Song period of the 12th and 13th centuries, many of the country’s most famous painters and poets lived here, seeking escape on the banks of the tranquil, willow-shaded West Lake while influential monks established temples with towering pagodas in the quiet hilltops nearby.

For generations, schoolchildren from all over China have grown up learning verses that were inspired by this place. One of the most famous poets, Bai Ju Yi, wrote, “Remembering the Fair South,/As always, it is Hangzhou I most recall:/ Amongst the mountain temples/ I search for the osmanthus petals/ From which the moon did fall.”

And although it has never been a common destination for foreign tourists, it made a lasting impression on those who discovered it. As Marco Polo described it: “In heaven there is paradise/ On earth, Suzhou and Hangzhou.”

Today, though Hangzhou is a teeming city of eight million, foreign tourists remain rare. In 2009 it attracted 63 million visitors — Venice, by comparison, draws about 20 million annually — but only 5 percent were from outside China.

That is primed to change, with a raft of new luxury hotels and a new high-speed trainarriving from Shanghai’s gleaming Hongqiao station. The train, which made its debut last October, means that the trip from Shanghai to Hangzhou is 40 minutes, compared with the three-hours-plus it used to take by car. And the voyage itself, which costs less than $20, exposes passengers to a fascinating montage of old and new China (new cookie-cutter cul-de-sacs emerge alongside derelict old structures that are quickly being razed), all at 250 miles an hour.

Despite its size, the city is laid out well for visitors, with the new and quickly growing part of Hangzhou separated from the more ancient sites by a large lake and a series of medieval canals and craggy hills in the distance. Yang Yi, a journalist for The City Express, took me on a tour of the historic He Fang Street with its bustling wood teahouses, noting his amazement and pride at the speed of development. “On the south edge of the city there used to be only acres and acres of peasant land on the opposite side of the river,” he said. “Now I just see more and more buildings.”

But even if Hangzhou’s former status as a peaceful refuge from the rough and tumble world of politics and business may be mostly symbolic at this point, it still carries heavy spiritual weight and the burgeoning middle class is streaming in to see the temples, lake and the sheltered pagodas. To me, observing the first generation of domestic travelers enjoying their leisure time and taking in the nationally beloved sites was every bit as interesting as the sites themselves.

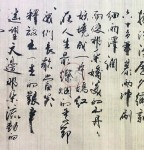

It is clear that tourism is booming and new attractions are being opened to complement the city’s must-see staples: The city’s bike paths (dotted with the bright red bicycles provided by the city for only 50 cents a day) are crowded with Chinese tourists from Shanghai, Tianjin and Beijing; beautiful old-style restaurants like Dragon Well Mansion (notable for its excellent local and organic ingredients) serve up dishes like sea cucumber and poached river fish to well-heeled Chinese tourists showing off newfound wealth; and new museums like Zhejiang Art Museum, which opened in 2009, mix contemporary work with traditional exhibits and calligraphy in a bid to attract a younger crowd.

Not surprisingly, luxury hotels have also arrived. The Shangri-la, Aman resorts, Banyan Tree and Four Seasons have all unveiled outposts in the last few years, and the Angsara plans to open a hotel this year. The new resorts, removed from the new part of the city, have all positioned themselves to be quiet enclaves in the hubbub: the Amanfayun resort has reinvented a former tea village near Lingyin Temple and turned it into a series of pared-down villas with a destination spa and dim sum restaurant, and the Banyan Tree sits within one of the country’s most impressive wetland parks. The newest arrival, the Four Seasons, sits on a quiet bank of West Lake with over 10 acres of landscaped gardensand pavilion-like structures.

But even outside the hotels’ grounds, it is still possible to find moments of quiet inspiration. From a simple jetty, an old Chinese boatman took us out on a sampan, one of the traditional wooden boats that is Hangzhou’s equivalent of a gondola. The sound of paddling was the only thing we heard as we passed under stone-arch bridges and alongside banks of bamboo and willow trees. Skeleton-like branches peeked out of the mist; high up in the hills a lone pagoda kept watch over the lake; a fishing boat sat almost motionless in the water; a songbird rested in a willow tree. We passed secluded spots with names like Lotus on the Breeze at Crooked Courtyard, Viewing Fish at Flowers Harbor, Melting Snow at Broken Bridge and Listening to the Orioles in the Willows.

And then our lonely boat entered the main part of the lake. Pagoda-style ferries bobbed on the water, locals were taking in the sights of the smaller inner island of Three Moons Mirroring the Moon, where some set up impromptu picnics. Everyone, it seemed, wanted to be a part of Hangzhou’s new poetry.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|

- 2020-08-09 - 读海(之二)

- 2020-08-09 - 读海(之一)

- 2020-07-27 - 丁仕美书法及诗歌作品《纯情吟》

- 2020-05-14 - 右玉城

- 2020-01-28 - 血墨

- 2011-03-27 - Qinyuanchun, Mount Heng By Ding Shimei

- 2009-08-13 - 水调歌头 —谒关帝

- 2009-07-28 - 河东行--长诗

- 2008-11-19 - 西北咏风 - 五律

- 2008-11-15 - 琵琶吟