137cm X 53cm

Because turtle shells as well as bones were used, the oracle bone script is also sometimes called shell and bone script. As the majority of oracle bones bearing writing date to the late Shāng dynasty, oracle bone script essentially refers to a Shāng script.

The history of oracle bones is at once long and brief. Although the “bones” are well over 3000 years old, the artifacts we now so designate were not discovered and identified as such until 1899. It was in that year that Wang I-jung, minister of the War Department, went to a traditional Chinese pharmacy to obtain medicine for an ailment. Among the items provided to him he found a bone with what looked like archaic script on it. Instead of grinding the bone to powder, as medically directed, Wang brought together his scholar-friends to study the bone and its inscription instead. No further mention is made of how Wang’s health fared. However, his and his friends’ interest in the mysterious “dragon bone” did lead to a search for the place of origin of the bone, and to extensive excavation—legal and otherwise—to feed the desires and curiosity of scholars and collectors (to say nothing of the pocketbooks of antiquity dealers). It was not until 1928 that the Academia Sinica initiated the first of a series of official, and professionally conducted excavations. By this time, it had been confirmed that the place of origin of the bones lay in the village of Xiaodun, the confirmed site of Yin, the last Shang dynasty (c. 1200-1027 BCE) capital, near Anyang in northern Henan province.

A number of animal parts were used for these oracle bones, from a variety of different animals, though most commonly the ox and the turtle. Of the bovine bones, a number of different ones could be used, as long as they had a sizable enough flat surface. Most frequently the scapula or shoulder bone (jianjia) was used. Of the turtle both the carapace or top shell (beijia) and the plastron or bottom shell (fujia) were used. Most pieces in the Starr Library collection are scapulae.

Oracle bones are important in a number of ways. First of all, they carry the earliest known form of written Chinese, and thus are of great interest to scholars of language. However, their import goes well beyond the merely linguistic as the interpretation of their textual content has helped explain elements of early Chinese culture and has played a large role in confirming ancient historical facts, especially as it pertains to Shang court life. In fact, the information to be found on the oracle bones helped confirm the historicity of the Shang dynasty itself, which until the bones’ interpretation was all but certain. For instance, one of the fragments in our collection is part of one of two scapulae recording the complete tables of the royal genealogy of the house of Shang. Scholars have been able to verify that the table as it appears on these bones (other parts are in different collections) is almost identical with that given in Sima Qian’s Shi Ji, and hence functions to confirm the accuracy of the traditional historical accounts.

As the name by which they are now generally referred to already indicates, oracle bones were used for pyromancy-type divination purposes conducted by and for the Shang kings. It has become clear that such divinations were performed on a very regular basis regarding every aspect of court life and activities affecting the court, from religion and politics to warfare, family matters, the weather, and much more. Preparations for oracle bone pyromancy—only one of a number of different divination techniques used in the course of Chinese history—involved sawing, scraping, and smoothing the bones with bronze tools, after which a series of pits (zuan)—round or oval indentations—were created in the back. Occasionally, marginal “administrative” notes were inscribed on the bone before the pits were created. Once prepared in this manner, a question could be raised, whereupon heat was applied to the thinned surfaces of the pits causing the bone to crack. The form of these cracks would then be interpreted as the divine answer. Subsequently, the divination would be engraved on the bone, frequently accompanied by confirmation of how the divination had come true.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|

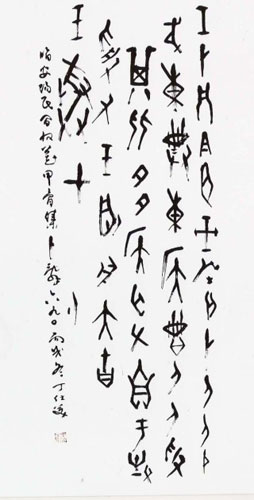

- 2008-11-28 - 丁仕美大篆书法横幅,释文:“小胜靠谋,大胜靠德。”

- 2008-11-27 - 丁仕美鸡毫隶书书法对联《万顷烟波鸥境界,九秋风露鹤精神》

- 2008-11-26 - 丁仕美大篆书法横幅, 释文:“人杰地灵”

- 2008-11-25 - Confucius: The Doctrine of the Mean , Big Seal Script.

- 2008-11-23 - The essence of all God's creation, Seal Script Banner

- 2008-11-21 - Cursive Script, “Buddha”,

- 2008-11-19 - Serenity in Chinese Calligraphy, Big Seal Script Banner

- 2008-11-18 - Astrology in Chinese Calligraphy, Big Seal Script Folding Fan

- 2008-11-17 - Blessing in Chinese Calligraphy, Big Seal Script

- 2008-11-14 - Longevity in Chinese Calligraphy, Cursive Script.