The Orchid Pavilion (Lantingji Xu) by Wang Xizhi (Chinese: 王羲之, 303–361) was a Chinese calligrapher, traditionally referred to as the Sage of Calligraphy (書聖), who lived during the Jin Dynasty (265–420).

None of his original works remain today. Some of his best writings were preserved on carved stone tablets, Stone rubbings taken from them have been reproduced and reprinted widely; they have been studied by generations of students and used as examples to learn and practice the art of calligraphy.

The Orchid Pavilion (Lantingji Xu) (simplified Chinese: 兰亭集序; traditional Chinese: 蘭亭集序; pinyin: Lántíngjí Xù; Wade–Giles: Lant'ingchi Hsü; literally "Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion") or Lanting Xu (蘭亭序) is the most famous work of calligraphy by Wang Xizhi, composed in year 353. Written in semi-cursive script, it is the most well-known and well-copied piece ever. It describes a gathering of 42 literati including Xie An and Sun Chuo (孙绰) at the Orchid Pavilion near Shaoxing, Zhejiang, during the Spring Purification Festival to compose poems and enjoy the wine. The gentlemen had engaged in a drinking contest: wine cups were floated down a small winding creek as the men sat along its banks; whenever a cup stopped, the man closest to the cup was required to empty it and write a poem. In the end, twenty-six of the participants composed thirty-seven poems.

The preface consists of 324 Chinese characters in 28 lines. The character zhi (之) appears 20 times, but no two look the same. It is also a celebrated work of literature, flowing rhythmically and giving rise to several Chinese idioms. It is a piece of improvisation, as can be seen from the revisions in the text.

Emperor Taizong of Tang liked Wang's calligraphy so much that he ordered a search for the original copy of Lanting Xu. According to legend, the original copy was passed down to successive generations in the Wang family in secrecy until the monk Zhiyong, dying without an heir, left it to the care of a disciple monk, Biancai. Tang Taizong sent emissaries on three occasions to retrieve the text, but each time, Biancai responded that it had been lost.

Unsatisfied, the emperor dispatched censor Xiao Yi (Tang Dynasty) who, disguised as a wandering scholar, gradually gained of confidence of Biancai and persuaded him to bring out the "Orchid Pavilion Preface." Thereupon, Xiao Yi seized the work, revealed his identity, and rode back to the capital. The overjoyed emperor had it traced, copied, and engraved into stone for posterity. Taizong treasured the work so much that he had the original interred in his tomb after his death. The story of Tang Taizong seizing the Lantingji xu has since been the subject of numerous plays and novels.

Numerous tracing copies and other forms of duplications such as rubbings exist today.

Translation of The Orchid Pavilion:

In the ninth year of the reign Yungho[A.D. 353] in the beginning of late spring we met at the Orchid Pavilion in Shanyin of Kweich'i for the Water Festival, to wash away the evil spirits.

Here are gathered all the illustrious persons and assembled both the old and the young. Here are tall mountains and majestic peaks, trees with thick foliage and tall bamboos. Here are also clear streams and gurgling rapids, catching one's eye from the right and left. We group ourselves in order, sitting by the waterside, and drinking in succession from a cup floating down the curving stream; and although there is no music from string and wood-wind instruments, yet with alternate singing and drinking, we are well disposed to thoroughly enjoy a quiet intimate conversation.

Today the sky is clear, the air is fresh and the kind breeze is mild. Truly enjoyable it is sit to watch the immense universe above and the myriad things below, traveling over the entire landscape with our eyes and allowing our sentiments to roam about at will, thus exhausting the pleasures of the eye and the ear.

Now when people gather together to surmise life itself, some sit and talk and unburden their thoughts in the intimacy of a room, and some, overcome by a sentiment, soar forth into a world beyond bodily realities. Although we select our pleasures according to our inclinations—some noisy and rowdy, and others quiet and sedate—yet when we have found that which pleases us, we are all happy and contented, to the extent of forgetting that we are growing old. And then, when satiety follows satisfaction, and with the change of circumstances, change also our whims and desires, there then arises a feeling of poignant regret. In the twinkling of an eye, the objects of our former pleasures have become things of the past, still compelling in us moods of regretful memory. Furthermore, although our lives may be long or short, eventually we all end in nothingness. "Great indeed are life and death", said the ancients. Ah! What sadness!

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|

- 2008-12-18 - 唐朝颜真卿《颜氏家庙碑》(780年),楷书

- 2008-12-18 - 唐朝怀素《自叙帖》(777年),草书

- 2008-12-16 - 丁仕美行书书法对联《溪水、远山》

- 2008-12-15 - Li Qi Stele(Bei) , 156AD, Han dynasty, Clerical Script

- 2008-12-13 - 秦朝《泰山刻石》(公元前219),小篆

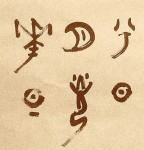

- 2008-12-10 - 殷墟甲骨文《祭祀狩猎涂硃牛骨刻辞》

- 2008-12-05 - As Peace as Abyss in Chinese Calligraphy, Big Seal Script Banner

- 2008-12-03 - 丁仕美草书书法横幅,辛稼轩《青玉案·元夕》

- 2008-11-30 - 丁仕美大篆书法扇面《无为大道,平等不二》

- 2008-11-28 - 丁仕美大篆书法横幅,释文:“小胜靠谋,大胜靠德。”